|

The abundance of the Marula fruit around Singita Sabi Sand, South Africa, this winter proved to be a great excuse for some elephants to party. Like apples on the ground, Marula fruit ferment after they fall off a tree. An African legend describes the results, and these photos provide the evidence, showing the massive pachyderms as they get hammered. In fact, eyewitnesses described the elephants stumbling, falling over and otherwise displaying signs of boozing familiar to humans.

0 Comments

There are endless arguments for why people drink, the simplest being that alcohol is tasty and it makes us feel good. But those reasons do not address the ultimate explanation for why our brains evolved to like alcohol in the first place, at least according to Robert Dudley, a professor of biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of "The Drunken Monkey." Dudley's drunken monkey hypothesis is the first attempt to place alcoholism in an evolutionary context. In a 2004 paper, he argued that modern patterns of alcohol consumption and abuse have a biological basis that can be traced to our fruit-eating primate ancestors. Hard-Wired For BoozeSugars in fruits, grains, and nectar are naturally turned to ethanol by yeasts during a process known as fermentation. The earliest archaeological evidence suggests, based on chemical residues from pottery jars, that humans did not start fermenting honey, rice, and fruit to produce alcoholic beverages until 9,000 years ago. But these fermented beverages were probably not our first exposure to alcohol, according to Dudley. Our preexisting taste for booze likely developed tens of millions of years ago in our primate ancestors, who survived mostly on fruits. As fruit ripens, more alcohol is created by the yeasts. When a fruit starts to seriously rot, it can contain up to 8% ethanol, although most ripe fruit contains less than 1%. Dudley's theory suggests that the alcohol concentration of ripe fruit would have served a purpose for both the fruit-bearing plant and the primate. In tropical forests, fruit can be hard to track down. However, the scent of alcohol from ripe fruits travels long distances, and may have helped primates to find their next meal. Being attracted to the scent of ethanol from ripe fruits would have been evolutionarily adaptive, enabling the primates to find fruit easier. It was also helpful to the plants, because the primates helped to disperse the seeds in the fruit. But the gains of eating these alcoholic fruits doesn't end there. Once digested, the theory goes, the alcohol would have stimulated feeding, encouraging the primates to "gobble up the food before anyone else got to it." Humans know this feeling today as the aperitif effect, which you may have experienced if you've ever had a cocktail before a meal and found yourself hungry. Or craved cheese fries after a night out. Modern Problems Primates probably weren't getting wasted, because fruits house only tiny concentrations of alcohol compared to today's drinks. In one study, Dudley found that the pulp of ripe palm fruits contained ethanol concentrations of 0.9% on average. Most beers have an alcohol strength of 4% and wine usually 14%. This could explain why a little bit of alcohol can be healthy, he said. The problem today is that humans aren't drinking alcohol in small amounts. Much like the story of sugar — which in ancient times was limited — alcohol is not only plentiful but, thanks to distillation, available in much higher concentrations than found in fruit. Our bodies have preserved the biological urge to drink from when alcohol sources were few and far between, even though we live in an age where the supply is unlimited. Read more: http://www.businessinsider.com/why-we-evolved-to-drink-2014-4#ixzz3Gq9Ia6IH  Milk straight from the source contains a variation of vitamins, minerals, fats, sugars, and other factors that promote optimal growth, development, and behavior in babies. Not only does the nutrient content of the milk change over time as the baby grows, but the milk’s composition will actually differ based on the gender of the child. In a variety of mammals, including humans, gender also plays an important part in milk composition. Males, who tend to be more muscular, require additional fat and protein. While the fat content in the milk females drink isn’t as high, they tend to consume more milk per meal and will nurse longer. A 2012 study led by Masako Fujita from Michigan State University published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology showed that human mothers produce milk with 2.8% fat for sons and 1.74% for daughters. In extremely impoverished locations where infant mortality is high, the fat content is higher for girls. A new study has shown that these differences may very well begin during fetal development. The study was led by evolutionary biologist Katie Hinde from Harvard University and was published in PLOS One. She presented her results this past Saturday at the AAAS 2014 Annual Meeting. The differences appear to begin during fetal development, according to Hinde’s study. Hinde analyzed 2.39 million lactation records from 1.49 million dairy cows and determined that those who had birthed females produced an average of about 445 kg (980 lbs) more milk than those who birthed males, over a two year lactation span. Even if the mother and calf were separated shortly after birth, the volume differences persisted. For cows, however, gender does not impact nutrient content. For some animals, such as rhesus macaques, social status within the group is passed down from generation to generation. Previous research from Hinde has found that young female rhesus macaques get higher levels of calcium than their brothers, giving them stronger bones and potentially allowing them to reach sexual maturity more quickly. Because females cannot reproduce throughout their entire lives, starting early is an advantage. However, the males receive more cortisol, which helps to regulate metabolism and temperament, allowing them to grow up strong and sire more offspring. Breast milk is hardly the static, homogenous liquid we are most familiar with from the store. Though the ability to nurse our young is one of the defining features that makes mammals distinct from every other class of animal, there is still an incredible amount about it that we are just discovering. Learning more about how the breast milk is formulated inside the mother’s body will allow us to better understand the ever-changing nutritional needs of babies and could even allow commercial formulas to be reconfigured to better nourish infants when breastfeeding is not an option.  Activity in certain regions of the brain can predict whether you'll like a new song enough to buy it, whether it's indie rock like Florence + The Machine's "Drumming Song" or experimental electronica like Ratatat's "Neckbrace." Those are just two songs used in new research that explains how new music rewards the brain. The study found that the more active the nucleus accumbens (a small area deep in the brain), the more likely people are to shell out cash for new music. This willingness is especially strong when the nucleus accumbens interacts with a brain region that stores memories of old music. The study helps explain how something as fleeting and intangible as a string of musical notes can be so rewarding, said study researcher Valorie Salimpoor, a doctoral student at McGill University in Canada. [Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind] "It's all happening in your head. You have nothing to show for it," Salimpoor told LiveScience. "But somehow, because we have the cognitive resources to be able to process and appreciate these temporal sound patterns, we can experience really intense emotions from them." The draw of new music Music seems a uniquely human phenomenon, and it appears across cultures. In fact, a study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in December 2012 found that even across vastly different cultures, people express primal emotions through music in strikingly similar ways. Music is known to engage emotion-processing regions of the brain, and Salimpoor and her colleagues had previously found that music perceived as pleasurable triggers the release of dopamine in the brain, a neurochemical associated with feelings of reward. Food and sex, which are necessary for survival and reproduction, also trigger dopamine release. That earlier study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, found that people didn't only receive jolts of dopamine at their favorite parts of a song; they got dopamine boosts right before, too. The finding suggested that anticipation is a major part of the pleasure derived from music, but it wasn't clear from where the anticipation was coming. "Are you anticipating your favorite part because you know it's coming up, or is it the case that you have some general knowledge of music based on all your previous experiences?" Salimpoor said. To find out, Salimpoor and her colleagues recruited 126 participants and whittled them down to a group of 19 who had very similar tastes in music — they turned out to be lovers of electronica and indie tunes. The researchers used music-recommendation programs to find new songs these participants had never before heard, and then had them listen to those songs for the first time in a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine (fMRI). [Brain Mixtape: List of Songs Used in the Study] Rewarding notes As the participants listened, researchers used the fMRI to track blood flow to various brain regions; this blood flow, in turn, is correlated with activity in those regions. After hearing a song clip, participants could choose to buy the tune with their own money, bidding to spend either 99 cents, $1.29 or $2, depending how much they'd liked it. The researchers found a strong link between how much a person was willing to spend on a song and the nucleus accumbens, in that a busier nucleus accumbens was related to more willingness to drop some cash. This brain region is known to be associated with reward, particularly forming expectations of reward. "It's really cool, because it's suggesting that as we're listening to new music, we're constantly making predictions," Salimpoor said. "This really links back to our previous study of anticipation and why it would play a role in music." What's more, as people were willing to spend more money on a song, their nucleus accumbens showed greater co-activity with another brain region called the superior temporal gyrus. This is an auditory region that essentially stores sense memories of music heard in the past. If you've heard a lot of Western music, your superior temporal gyrus will have a different "library" than if you grew up listening to music from East Asia, for example. The study suggests that when you hear new music, your brain flips through this library, building expectations from templates of music heard before. If those predictions are confirmed or pleasantly subverted, you may find yourself loving the new tune. "We can look at music as an intellectual reward," Salimpoor said, adding, "It's essentially pattern recognition, and this is something humans are very good at." Several other brain regions were also linked with finding music rewarding, including the emotion-processing amygdala and two higher-level emotion-processing regions found in the frontal lobe of the brain. Another frontal lobe region, the inferior frontal gyrus, was also linked to finding music pleasurable. This area handles advanced thought, working memory and pattern sequencing. The fact that the brain recruits these advanced brain regions may explain why humans seem alone among animals in appreciating music, Salimpoor said. "We're able to obtain pleasure from a sequence of sound that has no inherent reward in itself," she said. Link to article here Link to article here

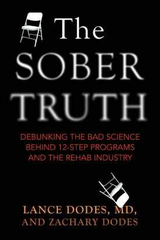

For alcoholics seeking a safe passage to sobriety, there’s a need for something to quiet the siren’s song of booze, and for generations two simple letters — “AA” — have been a beacon of hope. Alcoholics Anonymous is synonymous with getting help, the church-basement, default remedy for problem drinkers in real life and in the suds-soaked world of TV and movies. But for years addiction experts have debated the role and scientific effectiveness of AA, a fellowship founded in 1935 that relies on 12-steps aimed at a spiritual awakening. Some viewed AA as old-school, even cultlike. Others hailed it as a bedrock of recovery. Numerous studies have tried to pin down how well AA and the many 12-step groups it spawned, actually work. Dr. Lance Dodes is the most recent to wade into this debate in a new book, The Sober Truth: Debunking the Bad Science behind 12-Step Programs and the Rehab Industry. Dodes combed through more than 50 studies and found that the success rate for Alcoholics Anonymous is between 5 and 10 per cent, which he calls one of the worst in all of medicine. “I’m not trying to eliminate AA,” says Dodes, the former director of substance abuse treatment at Harvard’s McLean Hospital. “I’m just saying it should be prescribed to that tiny group who can make use of it. It’s terribly harmful when you send 90 per cent of the people for the wrong treatment advice.” AA doesn’t actually use the word treatment or therapy. Rather it’s about alcoholics helping one another beat booze by following the 12-step path that includes admitting powerlessness over alcohol, believing that a “Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity,” undertaking a “fearless moral inventory” and making amends. That can be hard to quantify, especially since members are anonymous. “The model has been so popular, so widely disseminated, that people believe it should be something that works,” says Dr. Bernard LeFoll, head of Alcohol Research and Treatment Clinic at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. But at this point, he says, we have neither definitive data supporting that it works nor studies about whom it most benefits. AA doesn’t have the answers either. “We are not a scientific or medical organization. We don’t do that kind of research,” says Jim, the public information co-ordinator at AA’s General Service Office in New York City, who maintains the anonymity tradition. AA’s sole data-gathering is a survey of 8,000 members in the U.S. and Canada every three years. As part of its tradition, the organization, with more than two million members in 170 countries, does not express opinion or engage in debate, he explains. But members will readily jump into the fray. “Yes AA works. I was in a very deep, dark, sad place. I walked into my first meeting, and people were so encouraging. It was a warm, friendly, safe place,” says John Fenn, now a recovery counsellor at Bellwood Health Services in Toronto. “I would never have been able to stay sober for 20 years without AA.” In his analysis of the research, Dodes found many problems. For one, much of the data was based on individuals’ self-reports, which are often unreliable. Another sticking point is how to define success. Many of the studies done by outside researchers only followed people for a year or less, explains Dodes. “That’s insane. It’s a lifelong condition,” he says. And, in what he calls a cardinal sin, some studies omitted the dropouts. The conclusions didn’t include the people for whom the program most likely didn’t work. While AA officially never comments, three AA members wrote a paper, “Alcoholics Anonymous Recovery Outcome Rates,” in 2008, refuting reports at the time of a very low success rate. The authors reiterated numbers espoused since AA’s early years as still the “best estimate:” For those who seriously work the program, the success rate is 75 per cent (that’s 50 per cent achieving immediate reward and another 25 per cent who slip then recover). But here’s an important caveat: Of all AA prospects, they say, about 20 to 40 per cent fall into that category of seriously trying the program. That leaves a lot of people not succeeding, likely dropping out. And they’re the ones who concern CAMH’s LeFoll. Since AA is so well known and easily accessible, it’s frequently the first place people try, he says. But if it doesn’t click for them, they may give up hope of recovery. They need full information about other available treatment, such as in-patient or outpatient individual therapy as well as group support that offers behavioural strategies, insights into addiction and relapse prevention tools.Historically the addictions field has pushed abstinence, but some programs now aim for reduction, a level of consumption that doesn’t produce harm. “The difficulty,” says LeFoll, “is that we can’t predict who can sustain reduction.” Advances in the neurobiology of addiction have led to more medications that deter the desire for a drink. Last year, CAMH opened the Alcohol Research and Treatment Clinic to improve access to these drugs, which have not been used by many physicians. One clinic patient, Terry, has started taking disulfiram, also known as Antabuse. It makes people extremely ill if they consume alcohol. “Now I don’t have to wrestle with wanting to drink. I know I can’t,” says Terry confidently. He’s going to AA meetings for extra support, but AA hasn’t helped him in the past. Over 30 years, he’s started AA and dropped out about 10 times. “I’m not a people person, not a joiner,” he says. Researchers do know that some kind of ongoing help boosts chances for long-term recovery. “We don’t oppose anyone joining AA,” says LeFoll. “We encourage people to build as much support as they can. We just want to give a broader view of all options and they can pick.” Most AA members don’t rely solely on fellowship. According to its 2011 member survey, the majority received additional treatment or counselling. Of the 62 per cent who got help after joining AA, 82 per cent said the added assistance played an important part in their recovery. “We’ve never claimed to be the only game on the block,” says the AA public information co-ordinator. “There isn’t a one-size-fits-all to that kind of personal struggle.” At Bellwood Health Services, an addiction treatment centre, clients go through group and individual therapy during their stay and can sign up for the aftercare program, but they are also encouraged to join a 12-step group for long-term support. Clients’ biggest objection is the religious aspect, says addiction counsellor David Paul. They don’t like the word “God” in the 12 steps or the idea of a Higher Power. The steps broadly define God “as we understood Him” and the Higher Power could be anything, he says, even the AA group itself. “I think at times people use God as an excuse,” says Paul. In the Greater Toronto area, there are nearly 500 AA meetings a week, including five for agnostics, aatorontoagnostics.com. While any 12-step program requires hard work, Dr. Peter Butt, an addiction specialist in Saskatoon, cautions against blaming the struggling addict for lack of effort. The focus should be: Why is this person struggling? Butt ticks through a list: Is there a concurrent mental health problem? Do they need medications for cravings? Do they first need help making their lives more stable? Maybe the person needs a 12-step meeting that’s a better fit. “Some people I’ve met in the 12-step community are very rigid, while others are the most compassionate of people,” says Butt, a representative on the Canadian Centre of Substance Abuse’s national alcohol strategy. “People do best when they have access to a spectrum of options,” he adds. “A 12-step program is simply one tool in the tool box.” That’s Steve’s attitude. He’s been sober 120 days and proud of it. To get there, he first tried AA but felt he needed a more intense intervention. After a stint of in-patient rehab, he now leans on a variety of supports: He’s back in AA, routinely sees a doctor specializing in addiction and also meets regularly with a group of non-AA recovering alcoholics who talk about their struggles. “I’m open to explore the best ways,” says Steve, as he eats lunch in a pub drinking a club soda. “Two months ago I could not have eaten here. I haven’t even looked over at the draft taps.” Link to article here  The idea that men are from Mars and women are from Venus, with male and female brains wired differently, is a myth which has no basis in science, a professor has claimed. Neuroscientist Prof Gina Rippon, of Aston University, Birmingham, says gender differences emerge only through environmental factors and are not innate. Recent studies have suggested that female brains are more suited to social skills, memory and multi-tasking, while men are better at perception and co-ordinated movement. However, speaking on International Women’s Day, Prof Rippon will claim that any differences in brain circuitry only come about through the ‘drip, drip, drip’ of gender stereotyping. “The bottom line is that saying there are differences in male and female brains is just not true. There is pretty compelling evidence that any differences are tiny and are the result of environment not biology,” said Prof Rippon. “You can’t pick up a brain and say ‘that’s a girls brain, or that’s a boys brain’ in the same way you can with the skeleton. They look the same.” Prof Rippon points to earlier studies that showed the brains of London black cab drivers physically changed after they had acquired The Knowledge – an encyclopaedic recall of the capital’s streets. She believes differences in male and female brains are due to similar cultural stimuli. A women’s brain may therefore become ‘wired’ for multi-tasking simply because society expects that of her and so she uses that part of her brain more often. The brain adapts in the same way as a muscle gets larger with extra use. “What often isn’t picked up on is how plastic and permeable the brain is. It is changing throughout out lifetime “The world is full of stereotypical attitudes and unconscious bias. It is full of the drip, drip, drip of the gendered environment.” Prof Rippon believes that gender differences appear early in western societies and are based on traditional stereotypes of how boys and girls should behave and which toys they should play with. Segregating the way children play – giving dolls to girls and cars to boys – could be changing how their brains develop, she claims. “I think gender differences in toys is a bad thing. A lot of people say it is trivial. They say girls like to be princesses. But these things are pervasive in the developing brain and stifle potential. “Often boys toys are much more training based whereas girls toys are more nurturing. It’s sending out an early message about what is expected in a child’s future.” Earlier this year Consumer Affairs minister Jenny Willott said that women were being forced into professions that paid less well because of gender stereotyping when they are children. Girls were often guided into low paying occupations like nursing because of the types of toys they were given to play with, she claimed. This led to an over-representation of women among nurses – and of men among engineers and physicists. Debenhams has stopped gender specific labelling of toys – Mark and Spencer was now its own brand of toys more “gender neutral”. Megan Perryman, who co-founded Let Toys Be Toys, a campaigning group against gender stereotyping said: "In our experience, children enjoy a range of toys and it's important they are encouraged to play with anything that interests them. “Telling boys not to play at being caring, or girls to avoid toys involving science or physical activity can only serve to limit their potential. Children learn these 'rules' of how to be a boy or girl at a very young age, via marketing, media and those around them. It can be upsetting to the child if their interests do not conform and can prevent them from being the people they really are." Link to article here  In a potentially seismic move, the National Institute of Mental Health – the world’s biggest mental health research funder, has announced only two weeks before the launch of the DSM-5diagnostic manual that it will be “re-orienting its research away from DSM categories”. In the announcement, NIMH Director Thomas Insel says the DSM lacks validity and that “patients with mental disorders deserve better”. This is something that will make very uncomfortable reading for the American Psychiatric Association as they trumpet what they claim is the ‘future of psychiatric diagnosis’ only two weeks before it hits the shelves. As a result the NIMH will now be preferentially funding research that does not stick to DSM categories: Going forward, we will be supporting research projects that look across current categories – or sub-divide current categories – to begin to develop a better system. What does this mean for applicants? Clinical trials might study all patients in a mood clinic rather than those meeting strict major depressive disorder criteria. Studies of biomarkers for “depression” might begin by looking across many disorders with anhedonia or emotional appraisal bias or psychomotor retardation to understand the circuitry underlying these symptoms. What does this mean for patients? We are committed to new and better treatments, but we feel this will only happen by developing a more precise diagnostic system. As an alternative approach, Insel suggests the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project, which aims to uncover what it sees as the ‘component parts’ of psychological dysregulation by understanding difficulties in terms of cognitive, neural and genetic differences. For example, difficulties with regulating the arousal system might be equally as involved in generating anxiety in PTSD as generating manic states in bipolar disorder. Of course, this ‘component part’ approach is already a large part of mental health research but the RDoC project aims to combine this into a system that allows these to be mapped out and integrated. It’s worth saying that this won’t be changing how psychiatrists treat their patients any time soon. DSM-style disorders will still be the order of the day, not least because a great deal of the evidence for the effectiveness of medication is based on giving people standard diagnoses. It is also true to say that RDoC is currently little more than a plan at the moment – a bit like the Mars mission: you can see how it would be feasible but actually getting there seems a long way off. In fact, until now, the RDoC project has largely been considered to be an experimental project in thinking up alternative approaches. The project was partly thought to be radical because it has many similarities to the approach taken by scientific critics of mainstream psychiatry who have argued for a symptom-based approach to understanding mental health difficulties that has often been rejected by the ‘diagnoses represent distinct diseases’ camp. The NIMH has often been one of the most staunch supporters of the latter view, so the fact that it has put the RDoC front and centre is not only a slap in the face for the American Psychiatric Association and the DSM, it also heralds a massive change in how we might think of mental disorders in decades to come. Link to original article here |

PsychLabLearning without thinking is Archives

October 2014

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed